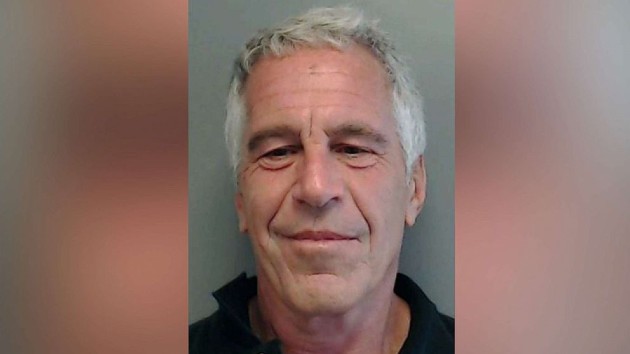

Key takeaways from the Justice Department review of Jeffrey Epstein sweetheart deal

Florida Dept. of Law EnforcementBy JAMES HILL, ABC News

(WASHINGTON) — Victims’ rights lawyers who have been battling the U.S. Department of Justice for a dozen years over the controversial “sweetheart deal” reached by federal prosecutors in Florida with convicted sex offender Jeffrey Epstein are blasting the department’s long-awaited review of the deal as “offensive” and a “whitewash.”

“I think, frankly, what we got was an effort to paper over what happened,” said Paul Cassell, a former federal judge who now represents Epstein accusers. “I think they’re trying to put the most favorable light on what’s clearly misconduct on the part of their attorneys.”

A 350-page report from the DOJ’s Office of Professional Responsibility (OPR), which was made public Thursday, determined none of the five federal prosecutors who were deeply involved in the Epstein investigation committed professional misconduct or violated any clear and unambiguous rules when they reached the deal without informing or consulting with victims.

Instead, the OPR report faulted former Labor Secretary Alexander Acosta, then the U.S. Attorney in Miami, for exhibiting “poor judgment” in deciding to resolve the Epstein case through a non-prosecution agreement and in failing to make certain the alleged victims were notified in advance of Epstein’s guilty plea in state court that ended the federal investigation.

“They just say he used poor judgment, and that’s their way of basically letting everyone off the hook while offering some sort of an olive branch to the victims that we acknowledge weren’t treated perfectly,” said Brad Edwards, who sued the DOJ in 2008 on behalf of Epstein accusers, seeking to invalidate the once-secret deal. “But nobody really did anything wrong. It’s really offensive. It’s hurtful.”

Jena-Lisa Jones, who has alleged Epstein sexually abused her when she was just 14, called the Justice Department’s conclusions “like another slap in the face” to victims.

“Poor judgment is cheating on a spelling test or speeding five miles over the speed limit. That would be poor judgment to me,” Jones said after attending a four-hour government briefing on the report’s findings at the FBI office in Miami. “I honestly don’t think that anybody will take responsibility in any sense, in any shape or form in the way that they actually should as adults.”

The OPR report, which took 22 months to complete, is not likely to be the last word on the Florida prosecutors’ treatment of Epstein, who was arrested last year by federal authorities in New York and then died while in custody in a Manhattan detention center.

Sen. Ben Sasse, R-Neb., who requested the department review after the Miami Herald’s in-depth reports on the Epstein case were published in late 2018, harshly criticized OPR’s conclusions and vowed to keep investigating what he labeled a “disgusting failure.”

“OPR might have finished its report, but we have an obligation to make sure this never happens again,” Sasse said in a statement.

Authorities in New York, meanwhile, have vowed to continue investigating anyone who may have conspired with Epstein or assisted him in the commission of his alleged crimes. Earlier this year, Manhattan prosecutors charged Epstein’s former girlfriend and close associate, Ghislaine Maxwell, with helping to facilitate and, in some cases, participating in Epstein’s crimes against three minor girls in the mid-1990s. Maxwell pleaded not guilty and has long denied any knowledge of Epstein’s alleged sex-trafficking. Her trial is scheduled for next summer.

And next month, lawyers Edwards and Cassell will argue before the 11th Circuit Court of Appeals in Atlanta that the Epstein deal, which also conferred federal immunity to any potential co-conspirators, should be rescinded because it was reached in violation of the federal Crime Victims’ Rights Act. The Justice Department has acknowledged that Epstein’s victims were not informed in advance about the deal reached with Epstein but contends that notification was not required because the federal government didn’t file charges.

Here are some key takeaways from the OPR report:

The lead prosecutor & FBI agents repeatedly pushed for Epstein’s arrest but were overruled by senior officials

Marie Villafaña, a career federal prosecutor assigned in 2006 to oversee the day-to-day Epstein investigation, repeatedly advocated for Epstein’s indictment and frequently clashed with her superiors over their decision to meet with Epstein’s high-profile defense lawyers, who were attempting to persuade the prosecutors to shut down the federal investigation and send it back to the state of Florida, where Epstein was under pending indictment for a single charge of solicitation of a prostitute.

In May 2007, Villafaña drafted a 60-count federal indictment of Epstein for “substantive crimes against multiple victims” and sent an 82-page prosecution memo to her supervisors, which included Acosta, then-First Assistant U.S. Attorney Jeffrey Sloman, and Matthew Menchel, the chief of the criminal division in Miami at the time.

According to the report, Sloman shared those documents with the head of the DOJ’s Child Exploitation and Obscenity Section in Washington, D.C., which reported back that while more research was needed, Villafaña’s work was “exhaustive,” “well done” and “correctly focused on the issues as we see them.”

Villafaña planned to file the charges on May 15, and the FBI was planning to arrest Epstein shortly thereafter in the U.S. Virgin Islands, where Epstein was acting as a judge at a local beauty pageant. But those plans were quickly shot down by Villafaña’s superiors, according to the OPR report.

“[A]fter learning that the FBI was planning a press conference for May 15, Sloman advised Villafaña that “[t]his Office has not approved the indictment,” the report said. “Therefore, please do not commit us to anything at this time.”

An FBI agent leading the agency’s investigation of Epstein told the OPR reviewers she and her co-case agent were “disappointed with the decision” not to arrest Epstein and her supervisor was “extremely upset” about it.

Acosta told OPR Villafaña was “very hard charging” but that her timeline for filing the charges was “really, really fast.” Menchel described Villafaña as “out over her skis a little bit” and ahead of Acosta, who needed more time to make a decision over how to proceed, the report said. But in the months that followed, Epstein’s attorneys heavily lobbied the prosecutors, often going around Villafaña or over her head when she rebuked the defense team’s demands for in-person consultations.

“As the lead prosecutor, Villafaña vehemently opposed meeting with Epstein’s attorneys and voiced her concerns to her supervisors, but was overruled by them,” the report said, noting that senior prosecutors viewed the meetings as primarily “listening sessions” that could be helpful for learning how the defense intended to attack the credibility of certain witnesses and perceived weaknesses in the case.

Villafaña said she feared her office was “going down the same path” the state of Florida had gone down in allowing Epstein’s defense attorneys to persuade prosecutors not to file serious charges, and she feared the delays might allow Epstein to continue to offend, the report said.

“Villafaña told OPR that she ‘could not seem to get [her supervisors] to understand the seriousness of Epstein’s behavior and the fact that he was probably continuing to commit the behavior, and that there was a need to move with necessary speed,’” according to the report.

Menchel told OPR that he didn’t recall Villafaña raising concerns about Epstein continuing to engage in criminal behavior and that “Epstein was ‘already under a microscope’ and it would have been ‘the height of stupidity’ for Epstein to continue to offend in those circumstances,” the report said.

In Villafaña’s view, the report said, if it weren’t for those early meetings granted to the defense team “the [office] would not have offered” Epstein a deal she believed “would never have been offered to anyone else” facing serious allegations of child sex crimes.

Villafaña’s disputes with her supervisors came to a head in July 2007, when she learned the office had proposed to Epstein’s lawyers that the federal investigation be resolved through a plea deal between Epstein and state prosecutors, a resolution Villafaña believed “didn’t make any sense” and “did not correspond” to Justice Department policy.

In an email to Menchel that is included in the report, she wrote: “[I]t is inappropriate for you to enter into plea negotiations without consulting with me or the investigative agencies, and it is more inappropriate to make a plea offer that you know is completely unacceptable to the FBI, ICE [Immigration and Customs Enforcement], the victims, and me.”

Villafaña also requested that all subsequent communications from the defense be directed to her and that she be afforded an opportunity to present a revised indictment to Acosta and other senior prosecutors to counter the defense arguments.

Menchel’s reply, the report said, began with a rebuke of Villafaña: “Both the tone and substance of your email are totally inappropriate and, in combination with other matters in the past, it seriously calls your judgment into question,” Menchel wrote to Villafaña.

“You may not dictate the dates and people you will meet with about this or any other case. If [Acosta or Sloman] desire to meet with you, they will let you know. Nor will I direct Epstein’s lawyers to communicate only with you. If you want to work major cases in the district you must understand and accept the fact that there is a chain of command – something you disregard with great regularity,” Menchel’s message said.

According to a footnote in the report, Villafaña believed Menchel’s email was “meant to intimidate” her and “put in [her] place,” but Menchel contended to OPR that Villafaña had a “‘history of resisting supervisory authority’ that warranted his strong response.”

Villafaña did not get the meeting she requested with Acosta. Later in July 2007, according to the report, Acosta made the decision to offer Epstein a deal that would end the federal investigation if Epstein agreed to a two-year term of imprisonment, registered as a sex offender and paid restitution to his victims. The deal was signed two months later.

Edwards, the lawyer for some of the alleged Epstein victims, told ABC News the OPR report bears out what he had long believed — that Villafaña was “a good person and a good prosecutor” who “tried to fight for the victims all along.”

Acosta decided to make the deal before the investigation was complete

Perhaps the most serious criticisms of Acosta’s handling of the Epstein case was the determination by OPR that Acosta decided to resolve it through the negotiated plea “before the investigation was completed,” a decision the report describes as “troubling” because the federal government was “uniquely positioned to fully investigate” Epstein’s alleged conduct not only in Florida but in other places where Epstein traveled and maintained residences, including New York, New Mexico and the U.S. Virgin Islands.

“As the investigation progressed, the FBI continued to locate additional victims, and many had not been interviewed by the FBI by the time of the initial offer. In other words, at the time of Acosta’s decision, the [government] did not know the full scope of Epstein’s conduct; whether, given Epstein’s other domestic and foreign residences, his criminal conduct had occurred in other locations; or whether the additional victims might implicate other offenders,” the report said.

Acosta’s decision came before Villafaña and the FBI could complete several potentially significant investigative steps, the report said, including interviews with alleged victims in other states and planned efforts by the FBI to try to persuade some of Epstein’s key assistants to cooperate with authorities.

“Although the FBI interviewed numerous employees of Epstein and Villafaña identified three of his female assistants as potential co-conspirators, at the time that [prosecutors] extended the terms of its offer, there had been no significant effort to obtain these individuals’ cooperation against Epstein,” the report notes.

Crucially, the report said, Acosta ended the investigation without obtaining potentially key evidence — the computers that had been removed from Epstein’s Florida home prior to the Palm Beach Police Department’s execution of a search warrant in 2005.

“The PBPD knew that Epstein had surveillance cameras stationed in and around his home, which potentially captured video evidence of people visiting his residence,” the report said. “There was good reason to believe the computers contained relevant — and potentially critical — information….[a]nd it was clear Epstein did not want the contents of his computers disclosed.”

Villafaña learned early in the investigation that the missing computers were in the possession of an individual associated with one of Epstein’s attorneys, and she tried repeatedly, but unsuccessfully, to get the defense attorneys to turn them over to investigators. She told the OPR “she had learned through law enforcement channels that the defense team had reviewed the contents of Epstein’s computers” and she believed the reluctance of Epstein’s attorneys to produce the computers “was further evidence” of their importance.

Villafaña ultimately obtained a grand jury subpoena for the computers, but Epstein’s attorneys fought the effort in court. The litigation was put on hold several times while Acosta contemplated how to proceed in the case, and the subpoena was eventually withdrawn as a condition of the non-prosecution agreement.

Acosta told OPR “he had no recollection” of Villafaña’s efforts to obtain the computers and objected to the report’s conclusion that he should have given greater consideration to pursuing the evidence before entering the deal with Epstein, the report said.

Villafaña told OPR that if the evidence on the missing computers “had been what we suspected it was … [i]t would have put this case completely to bed,” according to the report.

Prosecutors included a provision protecting alleged co-conspirators without giving it much thought

Among the most controversial provisions of Epstein’s deal was that it protected not only him but also any potential co-conspirators, known or unknown, specifically naming four women who were described as assistants to Epstein. That unusual clause has come to be regarded by many as being designed to immunize powerful and influential friends of Epstein who may have assisted him or participated in the alleged abuse of minors.

The OPR investigation found that the clause was inserted into the final agreement without much deliberation or consideration for how it might be interpreted in the future.

“OPR found little in the contemporaneous records mentioning the provision and nothing indicating that the subjects discussed or debated it — or even gave it much consideration,” the report said.

“Villafaña told OPR that she could not recall a conversation specifically about the provision,” the report said, “but she remembered generally that defense counsel told her Epstein wanted ‘to make sure that he’s the only one who takes the blame for what happened.’ Villafaña told OPR that she and her colleagues believed Epstein’s conduct was his own ‘dirty little secret.’”

At the time of Epstein’s arrest and leading up to his deal, Villafaña told OPR, there had not been public reports or allegations suggesting that any of Epstein’s “famous contacts participated in Epstein’s illicit activity” and that none of the victims interviewed before the deal was signed told the investigators about sexual activity with any of Epstein’s influential friends. Those allegations didn’t surface until years later, the report said.

At the time of the Florida investigation, “it was only Jeffrey Epstein,” Villafaña told OPR.

The OPR report said the review found no evidence indicating that “Epstein had expressed concern about the prosecutive fate of anyone other than the four assistants and unnamed employees of a specific Epstein company.”

The discussion in the OPR report regarding the co-conspirators’ clause does contain one passing reference to British socialite Ghislaine Maxwell, though she isn’t identified by name. And there’s no indication in the OPR report that prosecutors were focusing on her or considered her to be among those Epstein was seeking to protect.

“Villafaña acknowledged that investigators were aware of Epstein’s longtime relationship with a close female friend who was a well-known socialite, but, according to Villafaña, in 2007, they ‘didn’t have any specific evidence against her,’” the report said. “Accordingly, Villafaña believed that the only ‘co-conspirators’ of Epstein who would benefit from the provision were the four female assistants identified by name.”

The report does note, however, that one alleged victim interviewed by the FBI in 2006 “implicated the female friend in Epstein’s conduct, but the conduct involving the then minor did not occur in Florida.”

Some former prosecutors who were not directly involved in the Epstein deal told OPR the immunity provisions for any potential co-conspirators were “very unusual” and “a little weird.”

While OPR concluded that “the evidence does not show that Acosta, [Andrew] Lourie, or Villafaña agreed to the non-prosecution provision to protect any of Epstein’s political, celebrity or other influential associates,” the report faults Acosta, as the senior official overseeing the deal, for approving the provision without adequate consideration of the potential ramifications.

The U.S. Attorney’s Office “did not have a sufficient investigative basis from which it could conclude with any reasonable certitude that there were no other individuals who should be held accountable along with Epstein or that evidence might not be developed implicating others,” the report said. “The rush to reach a resolution should not have led [prosecutors] to agree to such a significant provision without a full consideration of the potential consequences and justification for the provision.”

Epstein was not an intelligence asset and did not provide assistance in other investigations

The OPR report also looked into allegations that have surfaced in press reports over the years that Epstein may have gotten special treatment because he was some sort of “asset” to U.S. intelligence agencies.

“Acosta stated to OPR that ‘the answer is no,’” the report said.

The OPR review also knocked down previous media reports that Epstein received leniency from Florida prosecutors by cooperating with federal prosecutors in New York who were investigating the collapse of investment bank Bear Stearns during the subprime mortgage crisis in 2008.

Villafaña told OPR she spoke to prosecutors in New York and was told they “had never heard of” Epstein and he was not a cooperating witness in the Bear Stearns case.

“In 2011, Villafaña reported to senior colleagues that ‘this is urban myth. The FBI and I looked into this and do not believe that any of it is true,’” the OPR report said, adding that Villafaña believed that the rumors of Epstein’s cooperation were “completely false.”

“OPR found no evidence suggesting that Epstein was such a cooperating witness or ‘intelligence asset,’ or that anyone—including any of the subjects of OPR’s investigation—believed that to be the case,” the report said. “It is highly unlikely that defense counsel would have omitted any reason warranting leniency for Epstein if it had existed. Accordingly, OPR concludes that none of the subjects of OPR’s investigation provided Epstein with any benefits on the basis that he was a cooperating witness in an unrelated federal investigation, and OPR found no evidence establishing that Epstein had received benefits for cooperation in any matter.”

Epstein hired multiple lawyers with personal connections to the prosecutors

Much has been made over the years of Epstein employing a “dream team” of highly skilled lawyers to help persuade federal prosecutors to drop their investigation. Epstein’s advocates included the famed Harvard law professor Alan Dershowitz and former U.S. Solicitor General Ken Starr, best known for his role as the independent counsel in the Whitewater investigation, which eventually led to the impeachment of former President Bill Clinton.

But the OPR report also details for the first time the breadth of the personal connections many of Epstein’s lesser-known defense lawyers had to the prosecutors conducting the investigation.

Among the first wave of attorneys to contact the U.S. Attorney’s Office on Epstein’s behalf were three former prosecutors, including two who were friends with Andrew Lourie, who was part of the supervisory team overseeing the Epstein investigation and the negotiations leading to the non-prosecution agreement. The third, former Assistant U.S. Attorney Lilly Ann Sanchez, had been a deputy chief of the major crimes section in Miami until leaving in 2005. Sanchez worked with Menchel during her tenure in the office, and Menchel told OPR the two had a “social relationship” that included “a handful of dates” over a two- or three-week period in 2003, before they mutually decided it “was probably best not to pursue” the relationship further.

During the negotiations over the deal, Epstein supplemented his team with Starr and Jay Lefkowitz, who had served in the administrations of former Presidents George H.W. Bush and George W. Bush. Lefkowitz and Starr had each worked previously with Acosta when he was a junior associate at the law firm of Kirkland & Ellis. Acosta met personally with Lefkowitz and Starr after the non-prosecution agreement was signed but while Epstein’s attorneys were pursuing further review of the deal’s terms at higher levels of the Justice Department.

Villafaña told OPR she believed Acosta was “influenced by the stature of Epstein’s attorneys” and that the defense lawyers convinced some members of the prosecution team that the case was “extremely novel and legally complex.”

“It was not as legally complex as they made it out to be,” Villafaña told OPR.

According to the report, Lourie disclosed his friendships with the two former prosecutors working for Epstein’s defense and sought guidance from a professional responsibility officer before continuing to supervise the Epstein investigation. He told OPR his “pre-existing associations” with the attorneys “didn’t influence anything.”

Menchel told OPR he and his colleagues recognized that Epstein was selecting attorneys based on their perceived influence with the office, but that he viewed this tactic as “ham-fisted” and “clumsy.”

“[O]ur perspective was this is not going to … change anything,” Menchel told OPR, according to the report.

The OPR report, however, did issue a mild rebuke of Menchel for failing to disclose he had previously dated Sanchez, a fact Acosta, Lourie and Sloman said they were unaware of at the time of the Epstein investigation.

“Although OPR does not conclude Menchel’s prior relationship with Sanchez influenced the Epstein investigation, OPR assesses that it would have been prudent for Menchel to have informed his supervisors so they could make an independent assessment as to whether his continued involvement in the Epstein investigation might create the appearance of a loss of impartiality,” the report said.

Menchel said by the time he got involved in the Epstein investigation in 2006, he was married and his relationship with Sanchez had “changed dramatically” after she left the office.

“[T]hat was three and a half years [prior] for a very brief period of time, and I don’t think I gave it a moment’s thought,” Menchel told OPR.

“Menchel stated that his relationship with Sanchez did ‘[n]ot at all’ affect his handling of the Epstein case,” the report said.

After examining the scope of the relationships, OPR said it could not “rule out the possibility” that prosecutors may have been willing to meet with Epstein’s lawyers because they knew them but concluded “OPR did not find evidence supporting a conclusion that the meetings themselves resulted in any substantial benefit to the defense.”

Acosta’s email inbox had a “data gap” covering several months

In conducting its review, OPR indicated it had access to more than 850,000 emails of the five prosecutors who were the subject of the review as well as six additional witnesses. But in an appendix to the report, OPR revealed there was an 11-month gap in Acosta’s incoming emails that coincided with the time frame of the Epstein investigation and negotiations over the deal.

After investigating the circumstances of the missing emails, which did not affect Acosta’s sent mail, the OPR determined it was most likely a “technological error” that caused those emails not to be preserved.

“OPR questioned Acosta, as well as numerous administrative staff, about the email gap,” the report said. “Acosta and the witnesses denied having any knowledge of the problem, or that they or, to their knowledge, anyone else made any efforts to intentionally delete the emails.”

After being informed of the “data gap” at a briefing for victims and their attorneys last week, Cassell said he was stunned, because he and his co-counsel Edwards have been seeking those emails for several years in their litigation on behalf of the victims, and they had never been told about the issue.

“Let’s assume it’s all innocent,” Cassell told ABC News. “Why weren’t we told, you know, years ago there was a technical glitch or something? Why is that just coming out now?”

Copyright © 2020, ABC Audio. All rights reserved.